- Home

- Ryan Campbell

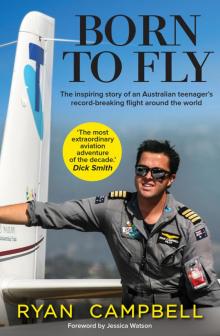

Born To Fly Page 3

Born To Fly Read online

Page 3

As I worked my way past goal after goal I kept on thinking about this. Not as a realistic adventure, more so a dream fuelled by curiosity. I never talked to anyone else about it – I didn’t want anyone thinking I wished to fly around the world myself. That would be crazy.

What made me think about this again in a different way was a conversation I had during Bob Tait’s theory course. I had been the only student who was studying the full seven subjects so I met lots of different pilots at different times. On this particular day I wandered over to a wooden table, sat down and began chatting to a guy called Cameron. He had a country bloke’s chilled-out attitude and a strong love for aviation. We exchanged the usual questions: ‘What do you fly?’ ‘Where do you want to end up?’ ‘I’m pretty sure I am going to fail the exam on Monday, are you?’

The conversation somehow turned to flying around the world. Cameron told me he knew a guy who had done it; he himself had thought about it and was very interested in the idea. I mentioned a similar interest and we shared a few ‘wouldn’t it be cool’ moments. Without another thought we went back to class. As I sat that evening and stalled on the idea of microwaving dinner, I thought about our conversation. I was intrigued that someone had the same interest as I did, yet had been just as cautious about mentioning it. How many more people were there with the same dream?

I put my highly refined detective skills to the test. I Googled: ‘How do you fly around the world?’ I sifted through the adverts for round-the-world commercial air tickets and found two websites. Earthrounders.com and Soloflights.org. I then found an article, ‘How do you fly around the world?’ My excitement and enthusiasm rose as I kept reading. When I found some good information I saved it in a folder. And then suddenly I thought: what am I doing? This is ridiculous. I closed the computer and turned on the TV.

Soon after I passed my commercial licence I received the final paperwork in the mail. After doing a few short courses on various areas of aviation I started work as a pilot with my uncle at Merimbula Air Services. Most of the time I flew up and down the Sapphire Coast giving tourists a glimpse of one of the most spectacular coastlines in the world. The odd charter, setting off to see what was behind the hills of the Bega Valley, was a welcome adventure.

Life began to settle down and although I was forever learning, the years of constant flight training were over for the time being. I began to meet new people within the industry and think about my next move, where I would go and what I would like to experience. I looked into the sensible options, the path worn by thousands of other pilots advancing to bigger and better aircraft as experience grew. I investigated courses overseas, thinking that maybe studying in the United States would be an option, and I also looked into a few avenues at home including the Royal Australian Air Force. I also kept putting information about flying around the world in the folder I had started on the night when I had first thought it might be possible. I watched documentaries on aviation, often more than once, and used my new-found inspiration to research a little more, to dream a little more. Eventually I had found out everything about it on the internet and read all I could find. I wanted to know still more.

I sat back and thought for a while, trying to work out a way to move forward while keeping my secret from people around me. All I needed was someone to steer me in the right direction. This person had to be an Australian who knew about flying around the world, and who had done so recently: any information from a pilot who had circumnavigated the globe many years ago might be of little use. I needed a recent earthrounder. And then I had an idea. I had read about two Australian men who had taken on the aviation world and won. Nothing wrong with starting at the top, I thought. I’ll just write to them.

CHAPTER

3

Closer to the dream

The first person I approached was possibly the most obvious one: Dick Smith. He is a household name as an entrepreneur, businessman and adventurer. Not only has he founded Dick Smith Electronics, Dick Smith Foods and Australian Geographic magazine, he has dedicated many years to the betterment of Australian aviation. He started learning to fly in 1972 and only four years later competed in his first air race, across Australia. In 1982, on the fiftieth anniversary of the first solo circumnavigation of the world by pioneering American aviator Wiley Post, he became the first person in history to fly a helicopter solo around the world.

Dick Smith has flown around the globe five times, once from the North Pole to the South Pole in a twin-engine aircraft, twice in a single engine Cessna Caravan and once with his wife Pip in a turbine Augusta helicopter, snapping over 10,000 photographs along the way. As I scanned through the information online, I was amazed at what he had achieved. He had an obvious passion for Australia and for aviation and I knew he lived not too far away. And, with five email addresses in hand – surely one of them would work – I sat at my computer and began to type:

Dear Dick Smith

My name is Ryan Campbell, I am 17 years old and live in Merimbula, NSW. I am a licensed Private Pilot with 200 hours and by April 2012 I will be a Commercial Pilot…

I summarised my life, my experience within aviation and my ambitions. I told him about the jobs I had taken – at the supermarket, washing dishes and washing semitrailers on weekends – so I could afford flying lessons, and the scholarship I had won. I told him that my long-term goal was a job in the airlines, frequent aerobatic flying and an active role in Youth in Aviation, somehow promoting flying to young people around the world, something that had not been done in the way I felt it should. And then I got to the pitch:

I am writing to you regarding the history making flights you have made throughout your life…I want to be the youngest pilot to fly solo around the world. I have always wanted to do this but it seems so far out of reach. For this reason I have kept quiet about my wish yet I am certain staying quiet is one thing I will regret when I am older. We get one shot at life and we are only young once, I have been blessed with an amazing start in aviation and I feel it is the best start I could have wished for and the best building block to begin a flight of this magnitude.

I am unsure about where to begin, the cost, the aircraft, the planning and even establishing the fact that this flight is possible. I feel I need to establish a better view on what is involved in the various aspects of this flight and the best way to begin thinking about it. I think by establishing a clear outline of what I am trying to achieve, partnered with the support of several individuals such as yourself, I will have taken the first step by setting a platform to build on, something I feel needs to be done sooner rather than later.

I want to be the youngest pilot to fly around the world; I want to use that fact to illustrate the accessibility of aviation to young Australians, and further abroad if possible. I hope you can understand the importance of this to me and provide your professional opinion. I would love the opportunity to meet if possible or talk further, and hope to hear from you soon.

Yours sincerely,

Ryan Campbell

I sat back and admired my handiwork, then scanned the letter carefully for spelling mistakes. It was only then I wondered what on earth I was doing. Did I really think I could just send Dick Smith an email? Part of me thought this was a ridiculous idea, but the other part overpowered that. After all, for years I had been saving page after page of information about aviation of any kind, I had found out whatever I could anywhere about flying solo around the world. So I hit ‘send’.

I didn’t want just to sit back and wait for a reply I doubted I would ever receive; there was another possible avenue of approach. During my hours of Googling I had stumbled across the names of Ken Evers and Tim Pryse, Australian pilots who had flown around the world together in 2010. I had scoured their website with envy. They had circumnavigated the globe for Millions Against Malaria, to increase awareness of malaria and raise funds for fighting it, and not only that but they had done it in the first Australian-designed and locally manufactured aircraft to fly around the worl

d. I had found Ken Evers’s details online and sent him an email similar to the one I had sent Dick Smith.

When I had finished I thought, well, that’s that. I’d done my best. I tried to remain optimistic, I didn’t let myself wonder what I would do if neither Dick nor Ken replied: I would worry about that when it happened, or rather didn’t.

But early in 2012 I received two emails. This was the first.

Dear Ryan

It sounds like a great project to become the youngest pilot to fly around the world. However, it is fraught with some problems – which I am sure you are aware of.

One is that in the United States a special law was enacted by their Federal Government to prevent aviation records being undertaken by young people. This was after a young person with an instructor and from memory his father on board crashed, killing everyone.

Personally I have never supported this move to having someone doing it younger and younger, because I suppose the limit becomes when the person is so young that they lose their life on the flight. Having said that, when I originally heard of Jessica Watson’s journey, I wasn’t that supportive, however after I had learned what a capable young lady she was, I ended up putting in some money to improve safety.

In my own flights, I waited until I had earned enough money to pay for the flight myself. However, I have supported other young people who have needed to raise money from donors to complete their flight. Of course, as you understand aviation records are extremely expensive.

So where do you go from here? Well I am not sure, but my suggestion is you try and get the hours up as much as possible and then see if you can get a wealthy company to support you. They could then get a return in publicity for your flight. Remember they will be of two minds in supporting you because they know that if something went wrong – and it can and even the best planned adventures can go wrong – they will be attacked and criticised by the media.

If you can get a major sponsor and your flight instructor, or people who know of your flying abilities, can verify to me that they believe you have a chance of safely completing the flight, I would certainly put in some money towards extra safety equipment. This would not be a large amount, as I don’t own a major company like Dick Smith Electronics any more that has this type of money available for adventure.

All the best with your ideas, I hope you can go ahead.

Regards

Dick Smith

Not too long afterwards I heard from Ken Evers. Ken’s email was short as he had been delivering an aircraft to India. But he said that he would help me in any way he possibly could and would speak to me once he was home.

I couldn’t believe it. Two of Australia’s leading aviators, and the word ‘No’ had never been mentioned, not once.

Ken was in contact as soon as he returned home. I don’t think he realised he was one of only two people in the world who knew about my idea. For four weeks we emailed back and forth, each message becoming longer and more detailed. Every time I opened my inbox I would learn something further about the requirements of flying yourself around the globe. At the end of the four weeks my crazy dream was becoming more focused, and I could see Ken had little hesitation in moving forward. At the end of the last email in our conversation was a single line: Let’s get this party started

I sat back and took a breath. I couldn’t believe that only four weeks after I had contacted him, Ken, who had done so much and was so busy, was willing to do all he could to help. Maybe, I thought, Ken would be my Don McIntyre. (With his wife Margie, Don McIntyre had supported Jessica Watson to the hilt. Don was a great adventurer who had done many amazing things: he and Margie had lived in Antarctica for a year in total isolation, he had sailed solo round the world, led sailing expeditions to Antarctica, flown round Australia in a gyrocopter and so much more.) Ken’s support was as incredible as Dick Smith’s.

Now I had someone to back me. I had the support of Dick Smith. I had the basis for a team. What now? There was one easy answer to that. I had to tell people what I wanted to do, the secret I had kept hidden for so long. They needed to know how much time I had devoted to this, how serious I was. Starting with Mum and Dad.

My mum is a ‘text me when you get there’ mum. If I ever forgot to do that, which I did just about anytime I went anywhere, I could be sure that the phone would ring three minutes after my predetermined and heavily documented arrival time. The ‘I drove slowly and just arrived’ excuse could be stretched only so far.

I have given Mum lots of other opportunities to practise her communication skills. I was the kid who said he didn’t need a list to remember four items to buy at the grocery store and returned home with three. The kid who left his school jumper at home, despite the best recommendations of the weather man and my entire neighborhood, and spent the day freezing. I was the kid who parked in a shopping centre car park, spent thirty minutes in the shops and two hours trying to find my car.

Knowing all this, I figured asking Mum and Dad whether I could fly around the world could only go well, right?

I pulled a folder from my cluttered drawer and emptied out the old schoolwork. The printer hummed away turning all my information-filled emails from Ken and the cherished reply from Dick into hard copy. All this was color-coded and in chronological order and placed back to back with all my previously accumulated information. The most important bits were highlighted. I had to make the information as simple and clear as possible. That way I figured Mum and Dad could read it faster, which in turn would reduce their chance of having heart attacks.

After dinner one night and making sure I dried the dishes – a strategic move, I might add – I asked Dad what he would say if I told him I wanted to fly around the world. Mum was sitting over at the dinner table listening in. Dad, who of course was a flyer himself, thought the idea was pretty cool. Mum joined the conversation with a similar view that it would be quite the adventure.

Okay. So here went.

I handed them the folder and explained the story. They read through the emails and slowly realised what I was telling them; that this was no crazy out-there idea that would be gone next week. They asked me a lot of questions, where did this idea come from? What made me really want to do this? How do you take a single-engine plane around the world? What did I see as a next step? I answered each questions as best I could based on what I had learned from Ken. Despite the research I had done, there is no doubt that none of us had any idea what was involved in flying around the world. Mum and Dad recognised that for me this was not an opportunity to ignore but one to follow up and see where it led, and that I had to find out myself. They knew I didn’t want to regret not having done it in later years.

We decided that a good first step was to talk to my Uncle Andy, an experienced commercial pilot, and to my flying instructor Alan. Folder in hand, I drove to the airport and my uncle’s company, Merimbula Air Services, as I was due to work that day anyway, checking out a new aircraft with Alan. It wasn’t the best time to give him my news, so I asked for a quick chat before the end of the day.

I flew north in the new aircraft while a curious Al sat in the other front seat. Seeing no better time than the present, he asked what I wanted to talk to him about. Short of having an impromptu lesson in skydiving there was no way I could escape. And so, nervously at first, I told Al the same story I had told Mum and Dad.

His response was fantastic. He said he believed I could do it, and encouraged me to have a go. I got the same response from my Uncle Andy. They could see the magnitude of the challenge, yet because they both knew my flying and more importantly my attitude towards flight, they saw no issue in moving ahead. Their belief and encouragement were wonderful, they just meant so much. And now I had a team, a team of seven – me, Mum and Dad, Alan, Uncle Andy, Ken Evers and Dick Smith. A team that would go on and grow into something beyond a number.

CHAPTER

4

Small steps

I loaded the Cessna with our overnight bags and strapped in. Mu

m hopped into the right seat while Dad and Uncle Andy stood by to see us off. Mum and I were off to Bendigo in Victoria, the home town of Ken Evers, my newly acquired mentor. My flight bag had a folder jam-packed with questions.

Still not being sure what flying around the world actually entailed, I looked forward to meeting Ken in person. I wanted to see the enthusiasm that had glowed from every email he had sent me, to find answers to the million questions now absorbing my every waking moment, and more than anything else to add some certainty to what had occurred over the last few weeks. In terms of detailed planning I was in limbo, eager to sit down with Ken and find out the next steps. I had sat down and laid out the research done to date, setting out what I thought I knew. The support team and I had all agreed that meeting Ken would give us some kind of initial direction to begin planning.

As we taxied to the end of the runway at Merimbula airport, I realised that we might have been heading to a meeting about flying around the world solo but this was the first time I had taken Mum flying outside the local area. We passed the familiar boundaries of the Sapphire Coast and flew across the white peaks of the Snowy Mountains, chatting away as the land flattened to vast flat stretches of countryside. Two and a half hours after takeoff we touched down in Bendigo, almost in the middle of Victoria – with a population of 83,000 not exactly a little Aussie country town. We unpacked, tied the aircraft down and made our way to our motel and dinner.

The next morning we waited at the kerb for Ken, who pulled up soon after to give us a lift out to his house. His number plates read ‘Avi8tor’, he was smiling eagerly and in an almost hyper manner he stretched out his hand and introduced himself. I was worried; even though we had spoken via email, the momentum that the flight would gather was dependent on Ken, more specifically it would depend on how our chat went throughout the day. Ken was a family man; he had a lovely wife and three young boys and was heavily involved in a career outside of aviation. The more I spoke with Ken the more I realised, regardless of where he was working that his passion was purely within aviation; stories flowed and the more we spoke the more excited we became. Ken had experienced what I was hoping to do, he was one of the very few who understood what was involved and although this included the associated dangers, risks and hardship, more importantly he understood the feelings of accomplishment, achievement and satisfaction, and the rare feeling derived from successfully flying an aircraft around the world.

Born To Fly

Born To Fly