- Home

- Ryan Campbell

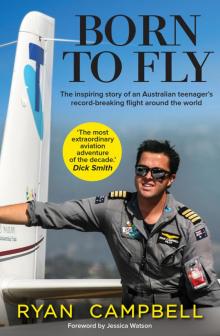

Born To Fly Page 23

Born To Fly Read online

Page 23

We took an air-conditioned mini bus to the terminal and walked to Customs, where my handler proceeded to escort me straight past a phenomenally long line of people and to the front of the queue. This Captain thing was kinda cool, I thought. Maybe I needed to dye my hair grey and find a comb.

After Customs I was driven to the motel, they sat me down, gave me a warm, wet face washer and took my bags, telling me, ‘You have a phone call, Captain.’ People called me? People knew where I was? I had moved up in the world that far? Wow. The caller could have been a telemarketer for all I cared. It turned out to be the handler back at Muscat airport to confirm fuelling and departure requirements.

After my phone call I went to my room. The humidity on the short walk from the air-conditioned lobby out into the open air stopped me in my tracks and I had to remove my glasses as they fogged up immediately. I found my room and saw my bags had beaten me there. At least that was cool. I ordered dinner and sent updates as I ate, answered emails and worked through the social media chatter. It was always a good feeling to read people’s comments regarding the flight and I missed very few during the entire journey. Before long I was in bed.

I had one full day in Muscat, the one day I would normally spend in refuelling and preparing the plane. My handler had told me that if I returned to the airport that day I would need to be in full uniform, obtain a full security clearance and proceed through normal security just to gain access to the plane. I thought about the options and worked out that even if we tried, it wasn’t 100 per cent confirmed that I would receive the clearance I needed. And so I made the decision to take the day off. I had my flight plans with me at the motel where I could study up on the next day’s flying and I would refuel the following morning nice and early before my departure.

This level of security, the language barrier and excessive use of the word ‘Captain’ was something I had been told to expect in some places, and evidently Muscat was one of them. This was why I dressed in a flight suit covered in Australian flags, bearing the words ‘Pilot’ and with the renowned four golden bars on my shoulders, something normally reserved for the guy with the neat grey hair. Wearing the uniform, I had been told, was an absolute must for the countries between Greece and Australia: I needed to show authority and rank. I remember telling Ken I would fly in a white shirt and black pants, I could even put the sponsors’ logos on my back! His answer was an unco-operative and stern, ‘No’. He had then unrolled his flight suit to show me what I needed to wear. Along with showing who was in charge of the aircraft, the uniform was fireproof and had more pockets than I had gadgets. This included an inside pocket to hide my passport and cash.

Less than a year after my journey ended I saw on the news pictures of a pilot sitting in his light aircraft on the ground in a foreign country, surrounded by camouflaged soldiers with automatic rifles. Each and every soldier had the barrel pointed at him. He had been intercepted by a fighter jet and told to land. He was in serious trouble. This type of ‘international relations’ as outlined in the movie Top Gun required a subtle approach in order to have a happy ending, and a few bars on the shoulders and a suit to show your rank and position were only going to help. Unfortunately for this pilot, he looked as if he was dressed to go to the beach. Nice sandals, though.

I took on the day, working hard to finish up the paperwork, emails and phone calls to square away fuel and clearances for the remaining legs to Australia, then I donned my boardies and hit the pool.

I ordered lunch, they dropped it by and I ate under the sun and by the water. I was sick of trying to convert currencies and I needed to eat. Why stress over exchange rates? I had a burger and chips, which was about the cheapest item on the menu. It was one of those cute burgers that fits in the palm of your hand, accompanied by a quarter of a potato surgically divided into small sections. I wasn’t fussed that the meal wasn’t too large and just hoped that ‘25’ in their currency somehow resembled ‘25’ in ours. It didn’t. I had just eaten the world’s most expensive hamburger. It made the fuel supplier in Jordan look like a charity.

After lunch and another swim I had one more job to do. The significant amount of US dollars carefully placed in the Cirrus had been whittled away by my experiences in Jordan and now I needed more. I called the front desk but after having no luck at the hotel itself I ordered a cab, figuring I would zip down to the servo to find the closest ATM.

I pulled on some casual clothes and grabbed my passport wallet, which held credit cards and a pen and paper. My passport itself was always in the flight suit and this wallet was the next most important item.

I hadn’t really been outside in Oman all that much and I took the short drive as an opportunity to video the surrounding city. I signalled to the cab driver to wait when we pulled up at the service station, zipped inside and started to withdraw the cash.

I needed $2,500 US to cover upcoming costs, including fuel, but this ATM produced only local currency and without a bank nearby it was my only option. I began but each transaction was limited to a certain amount, each card also had a daily limit and somehow I needed to keep note of how much had been withdrawn from where. With my pen and paper in hand I got stuck in. I soon found out that one $100 US bill somehow transferred into a thick wad of local cash around two centimetres thick. I placed it in the passport wallet and kept withdrawing cash, the wallet becoming thicker and thicker.

I walked out of the service station with the equivalent of a little over $2,500 in US dollars. In Oman that translates into a small briefcase of cash and I looked as if I had just robbed the place. A few people were shocked but none more than the cab driver as I climbed in with cash falling from the straining passport wallet. I had absolutely no excuse not to give this guy a tip.

The taxi driver dropped me at the motel, my handler was picking me up the following morning so I had nothing to organise except something to eat for dinner. I wandered downstairs to a restaurant, sat down and looked through the menu. After I had ordered, I suddenly realised I was past ready to go home.

I ordered the Australian sirloin steak with pepper sauce. As to how much it cost – don’t ask.

CHAPTER

22

Across the Indian Ocean

By now I had been away for just over two months. I calculated that I had been flying for about 150 hours. Only another forty or fifty to go before I was home.

I woke up in Oman early, not only because the day’s leg to Sri Lanka would be strenuous and long but also because the intense security and the inability to get to the aircraft on my day off in Muscat meant refuelling was best left for the morning of my departure.

I packed my bags and made my way to the lobby. Even in the early hours of the morning the humidity hit me like a thick wall of water. My handler picked me up from the motel, we got into a silver Hyundai and set off into the darkness. We chatted as we drove, and I told her I needed to find some form of food to take with me. This turned out to be quite a challenge at such an early hour. In the end we stopped at a service station, I wandered inside and bought a bunch of items that were far from the ‘ideal’ culinary choices as suggested in the food pyramid.

At the airport, security was as tight as I had expected. There was no doubt about that. We manoeuvered through the international terminal, again lugging the bags and equipment. My passport was examined and the paperwork and General Declaration forms signed: the most emotionless people seem to work in airport security, I have found. Then we headed onto the tarmac in the darkness, boarded a little bus and set off towards the Cirrus.

I spoke with the handler about refuelling. I had a long flight over water and through a part of the world where the weather could build significantly as the day wore on, and I really needed to be on time. I would unpack the plane while the handler organised the fuel truck and while the refueller filled the wings I could sort out payment, using the ridiculously large pile of cash I was still lugging around, before hopping up on the wing and filling the ferry tank myself. All I needed th

en was to strap everything in, pack my bags on and around the tank and set off. It sounded easy.

But no matter how well thought out your plan of action might be, if the fuel truck doesn’t turn up you might as well have stayed in bed. The Cirrus had been emptied, all the equipment was spread across the tarmac and we just stood by waiting. The departure time was nearing and I was frustrated but my handler was so apologetic that I could hardly feel bad, nor look annoyed.

The day’s flight was to take me through India’s airspace, not somewhere listed on the ‘places to fly before you die’ list I had compiled with information from a range of ferry pilots. I had heard many stories about issues transiting through India and descriptions of interesting moments from pilots who had decided to stop over on the mainland. Originally my flight route had included a potential landing at Calcutta and Bangalore. However, discussion among experienced pilots resulted in a plan that was probably more achievable and would – we hoped – produce fewer problems. One of the first steps was to substitute any Indian stopovers with two nights in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

As I sat inside a small office keeping a keen eye on the Cirrus and everything I owned scattered on the ground around it, I was becoming really anxious. A little over an hour later the fuel truck finally arrived. I double-checked it was an avgas truck: discovering that it contained jet fuel would have just topped off my morning.

Finally able to get things going, I looked at my watch and realised I had a little over forty minutes before my planned departure. I had become quite good at this ferry tank business and with the wings completely full I took over and filled the auxiliary tank. I was in a hurry and it was hot, I looked as if I had just ran a marathon but I had the tank full of fuel in record time. I asked for various items like a dentist yelling for a drill, and worked to secure the tank while people handed me bags and equipment. I had the tank covered, the bags on top and tarmac around the Cirrus clear. I was only half an hour late.

I threw copious amounts of cash towards the refuellers. They did not apologise for their delay and were less than grateful for the money, which was in the currency of Oman, not US dollars. Well, you can’t please everybody. I hopped into the plane and said goodbye, started up and pointed the air vents towards me before contacting air traffic control. I heard: ‘Victor Hotel Oscar Lima Sierra, please note the airport is closed from time 00 to time 30. Clearance and your departure will be available after time 30.’ It was two minutes past the hour, meaning the airport had just closed. Two minutes!

After a little more time spent in the picturesque office with an apologetic handler, I finally made it into the air and I couldn’t have been happier to leave. The early morning sun lit up the desert, which very quickly became the coastline and then the endless Arabian Sea.

I climbed through a layer of cloud towards 9000 feet and watched the day unfold as I worked through the first ferry fuel transfer. I had become quite comfortable with flying the Cirrus in the overwater ferry configuration – I had completed a takeoff at maximum weight out of Hawaii, I had successfully completed a number of ferry fuel transfers, and as for the HF radio, well, that could be worked out on the way. I would never completely understand or like using the HF radio but I had little choice. Always looking for a way to do things better, I had time to think as I cruised over the Indian Ocean.

Many months before, as Ken and I sat around the kitchen table planning the flight, we had spoken about this leg from Oman to Sri Lanka. This had been at a time where I was being drowned in new information, trying to find a way to remember it all, to place it in my mind and understand where and how it would apply to my flight. At the time we had discussed the implications of ditching the aircraft into the ocean.

Landing the plane on water was never a desirable situation, of course. However, the method of landing differed, depending on where the emergency took place.

The best ‘worse case’ would be to ditch into a smooth, warm lake in the USA and to be taken in by a loving family for a good feed and a hot shower. After that not so likely option, a ditching near the shore of a well equipped country such as the USA, Australia or anywhere in Europe would be the next best: somewhere allowing a state-of-the-art rescue to take place quickly. From there the options grew worse: a ditching near a less than well equipped country or island, in an area where radio coverage was limited to the HF, in the middle of an ocean where rescue crews would require extensive travel. The unpleasant possibilities were endless. One of the worst, however, was a ditching during the leg from Oman to Sri Lanka, the leg I was currently flying.

The reason for this could be stated in one word. Pirates.

I had watched the Pirates of the Caribbean movies. The pirates had seemed like good bunch of guys with a sense of humour and a drinking problem. However, I was soon told that those who cruised the Indian Ocean were far from being the good guys. They didn’t have impressive beards or hooks instead of hands or large sailing ships or copious amounts of rum. Instead, if you were forced to ditch the aircraft, they could target an activated distress beacon – the kind installed in the Cirrus. They would then carry out their own ‘rescue’. Although we could never know exactly what would happen, the meeting would be anything but hospitable.

As with all the potential issues our risk mitigation plan took into account the threats throughout the Indian Ocean. We worked out an alternative method of alerting emergency services that did not include the use of the emergency locater beacons, a plan that would use the support team back at home to our full advantage. You should have seen Mum’s face when Ken started the pirate conversation.

Meanwhile, here I was at 9000 feet and air traffic control had transferred me from the Middle East-based controllers to those in India. The HF was still a challenge to use; although set up within the Cirrus as well as it could be, the reception was average at best. And on top of that was the Indian accent.

I had one goal, to see the coast of India pass under the nose of the Spirit of the Sapphire Coast. The greater part of the water I had needed to cross would be behind me and Sri Lanka would be not too far away. My casual thoughts of Jack Sparrow and his pirate gang would be replaced by the thought of dry land, a bed and something to eat. After more than eight hours in the air daylight was fading. I should have already been on the ground but thanks to the refuelling operation in Muscat I would now be arriving at night.

There were dozens of boats floating well off the west coast of India and what I had thought were the lights of civilisation on the mainland turned out to be fisherman bobbing up and down in the ocean. However, before long the lights of a city became unmistakable. I was so close.

I was now back using the standard aircraft radios, chatting to a controller I could understand quite well and it was all fairly straightforward. I had arrived over the southern tip of India before turning right and aiming for Sri Lanka. I stared down at the lights, the dimly lit streets and the buildings crammed tightly together. Regardless of what I told myself, there was no way I could really comprehend that what I was looking at, below me, was India. Once over the water again I didn’t look back at the land at all. Instead I focused on the ocean in front of me and hoped to spot the lights of Colombo.

Finally I was told to descend, but into a cloudy, murky mess. The closer I came to land the darker the sky became; however, a few thousand feet above the ocean I broke free of cloud. The sky was pitch-black but I spotted a dark sliver of land littered with lights.

With little time for the relief I felt on seeing that fantastic sight and knowing I was across that patch of ocean, I was given a clearance to land and with an unexpected change of plans I turned over the coast to line up only a few miles from the runway. It was a monstrous piece of bitumen and think I could have taken off and landed the Cirrus several times before running out of the sealed, smooth tarmac. I slowed down, quickly ran through my checks and moments later the tyres screeched onto the runway. To the right of the runway centreline lay the all-too-familiar ocean but to the left was endles

s tarmac, a car park for aircraft. As the Cirrus slowed down I spotted a large airliner with ‘Sri Lanka’ written up the side. Unless he was also lost, I was fairly certain I had found Sri Lanka.

The control tower gave me taxi directions, a long-winded list of alphanumerical designators relating to different taxiways which I jotted down before looking at the chart for Colombo’s main airport and working out where I had to go. I soon found my handler, a small group of guys waved me in and waited as I shut down. As soon as the propeller stopped moving they began looking all over the aircraft before trying to peer into the cockpit. I hopped out and said hello. They were just as excited to be there as I was.

I was expecting to see a few familiar faces in Colombo. The 60 Minutes crew including Charles Woolley had flown across to film a few segments for the story that would air when I returned home. It turned out that the joys of airport security and obtaining clearances for filming, among a few other challenges, had made it too complicated for them to be on the tarmac when I arrived.

My handler, along with his very excited co-workers, took a few photos before they all grabbed one of my bags and helped me onto a bus. It was not just any bus, but a full-sized one used to shuttle an airliner load of passengers to the terminal. Tonight it held a kid who had hopped out of his toy plane along with his handler and a few bags.

We swished through security, which was a non-event where I just stood by and smiled, except when being compared to my passport photo, and did everything I was asked to by my handler. I could tell he had done this a time or two before and he was a serious kind of guy – finding someone like that was sometimes a good thing. We laid out a plan of action for the next day and decided on a time to refuel.

Born To Fly

Born To Fly