- Home

- Ryan Campbell

Born To Fly Page 12

Born To Fly Read online

Page 12

Having successfully completed three legs I was growing used to the discipline of planning while flying. The idea was to take the flight just one leg at a time. When one leg had been completed the next leg became the focus, not the one after, just the next leg alone. Continuing with this idea, I decided to split up the entire route into six sections.

1. Crossing the Pacific Ocean – From Australia to the mainland of the United States of America

2. Crossing the United States – From the west coast to the east coast then north to Canada via the world’s biggest airshow in Wisconsin

3. Crossing the North Atlantic – From Canada to Scotland via Iceland

4. Crossing Europe – From Scotland to Greece

5. The Middle East and Asia – From Greece through to Indonesia

6. Australia – From Indonesia to the west coast of Australia and east to Wollongong

Taking this into account, I had only two legs to go before the first section to the USA mainland was completed. I knew that those after the USA would be hard and relatively risky, but peace of mind came from knowing that the flight across America would be a well earned break and much less stressful than the Pacific had been.

I packed my bags little by little, making sure that my dinner of muesli bars was left loose. I would pack a few items and then pause to step on several large ants that wandered across the floor, pack a little more only to find more ants welcoming themselves into my room. When I was finished I sat on the edge of the bed and took off my socks, now covered in ants, before spotting a small crab scuttling from door to door. What sort of place was this? And what other creatures lurked in the room, including beneath the bed? I tried to go to sleep slowly, convincing myself that nothing could scale the bed legs. If I stayed up there and my socks stayed down there I was sure I would see the next morning.

It was dark when I the alarm woke me, really dark. At around 2am I got up, dressed and prepared as well as I could, then went down to the front desk and asked whether my flight plan could be faxed through to Hawaii. But the phone lines, or rather lack thereof, would not permit that. I called San Francisco air traffic control on the satellite phone, explained who I was and that I needed to submit my flight plan. With perfect timing, the satellite phone lost reception and contact so I redialled and started again. The air traffic controllers soon worked out what was going on, and five or six phone calls later they had jotted down the details and submitted the plan.

John drove me to the airport and we said goodbye. I started up the Cirrus and taxied towards the runway, still the lone aircraft on the island. I dialled the HF radio frequency for San Francisco and made a radio call to let them know I was taxiing for takeoff. As I completed the final checks and prepared for departure, one of the controllers told me that my flight plan route had me tracking through something called a SIGMET, which meant ‘significant weather’. Today’s SIGMET was for embedded thunderstorms towering from sea level to 60,000 feet, around twice the height a domestic airliner would fly.

Before I had a chance to panic the controller offered a solution: alternative tracking that would take me to the edge of the storm, around it and onto ‘the Big Island’ of Hawaii. I asked for the alternative details and sat ready with a pen but what I received were a bunch of latitudes and longitudes from the controller’s radar, not the GPS waypoints I had been expecting. I sat at the end of the runway with the engine running and absolutely no idea how to enter latitude and longitude figures into the avionics. Could I possibly take off? The alternative, I decided, was muesli bars for dinner and being attacked by the island’s crab population. I decided I’d give it a go.

But twenty minutes later the map showed that the newly entered waypoints derived from the provided latitude and longitude figures had seemed to work, taking me nearly 100 nautical miles to the right of my original course. That was okay with me.

The airstrip ran parallel to the coast, and as soon as I was airborne I slowly banked the Cirrus to the left in order to pick up the track to Hawaii. The aircraft’s instruments were showing towering figures, it was a hot and humid thirty-two degrees Celsius outside and the engine temperature had risen significantly. I had been told from the very beginning to keep that temperature within certain limits so I lowered the nose and let the aircraft speed up. Although the climb slowed down, the engine was now receiving more air and therefore, I hoped, cooling a little.

However, the oil temperature exceeded the limit. I was extremely worried but saw no other way of cooling it down. I reached behind me and pulled out the pilot’s operating handbook, the instructions for the aircraft. I looked through to confirm the maximum temperatures in which the Cirrus could operate. The owner’s original limits set were lower than the actual maximum temperatures, a good idea for a safety buffer but not so great just then. I continued the climb to 9000 feet above the sea, knowing that as I climbed the air would become cooler and therefore bring the aircraft’s temperatures and pressures back to normal.

I sat in cruise for a little while; the skies ahead were blue and everything seemed calm as I began my list of duties. Then, as I transferred fuel and argued with the HF radio, the sky ahead turned grey. To the right there was bright blue sky, yet to the left it was as dark as night. Large grey clouds had formed at a low level, above them the weather continued into the atmosphere but rain showers hindered the view. It looked okay for now so I continued.

I soon realised the weather to the left was definitely the storm cell I had discussed with air traffic control earlier that morning. The darkness and cloud were beyond anything I had ever seen. Although the edges were crisp and definite, allowing differentiation between the storm and the clear blue sky, the centre remained a murky grey mess that gave no indication of just where I could fly in order to remain clear and therefore safe. Although the air traffic controllers had sent me nearly 200 kilo-metres to the right I was still going to fly straight through it, a massive no-no. I called San Francisco and requested to fly a further 50 nautical miles to the right, and tracked across to the right visually. Although this took me away from the centre of the storm, I soon realised there were smaller storm cells that were unavoidable unless I tracked via Mexico. The aircraft was already being shaken up and down and side-to-side; I disconnected the unhappy autopilot and weaved my way through towering cumulonimbus clouds. Each time I could see where I was going I had to decide whether to fly left or right, depending on which direction I thought would be the smoothest and where the next cell sat. It was like playing chess while trying to cross a river on stepping stones. I only took a wrong turn once, choosing left when I should have gone right, and realised the error almost immediately as the plane began shaking again.

After what seemed like days, I weaved around a storm cell to see continuous blue sky ahead. I turned and looked back to see an angry wall of storms and a very dark sky, and I could not have been happier to be heading in the direction I was. I couldn’t believe just how suddenly the weather had cleared. I took a breath and focused on the few hours left before touching down in Hawaii.

I switched from the HF radio to the standard aircraft radios when told to contact ‘Honolulu Approach’, and just prior to letting them know where I was I tuned in the ‘ATIS’ frequency. The ATIS is an automated rotational message that gives weather and airport information for your arrival. Part of the message was: ‘Caution: volcanic ash in vicinity of Hilo International airport.’

No way! How cool was that? I had never been anywhere near a volcano, let alone flown past actual volcanic ash. I was really pleased, then I decided it might be a good idea to look out for the ash itself; it was after all the last thing I needed to fly through. In the distance I could see a layer of what looked like a dark cloud, it sat at my current height and stretched out over the water where it dissipated.

I called Honolulu approach, requested descent under the ash cloud and then switched across to the Hilo control tower. As I flew towards Hilo I began to skirt the coastline. In some places the ground was a

pitch-black colour with no signs of life anywhere nearby. This I gathered was dry lava; the tracks it had formed in around houses and over roads were easily visible.

I was slotted in in front of a Hawaiian Airlines jet, and just to be flying in the same airspace as a Hawaiian aircraft was exciting. I touched down in Hilo and taxied in, guided by air traffic control to Air Services Hawaii, the company looking after me during my stay. Ken, who had stopped in Hawaii with fellow pilot Tim, had told me a lot about Air Services Hawaii and my handler Shanna. It was good to know that someone who had been approved was waiting for me, but I was too focused on other things to be excited about meeting anyone.

I nosed the aircraft towards the marshal before bringing it to a stop and shutting down, sat quietly and waited for the US Customs officials to walk over to the aircraft. As Hawaii is a state of the USA I would pass through Customs here and not have to worry again until I left the US on my way to Canada. I had been told just how strict US Customs were and had seen the amount of paperwork and prior approvals involved in transiting the country. I was fairly sure I had it all, including a small hard-to-get sticker attached to the outside of the aircraft. The only problem was that half the sticker was now missing, thanks to the battering the Cirrus had taken in the storms.

The Customs guys were fine. I waved my can of insecticide, showing that I had again sprayed the cabin prior to descent – just a few sprays and not the entire can this time – and only then was I allowed to open the door. I hopped out and waved to Shanna, whom I guessed correctly was a young woman holding a lei and smiling broadly, and then waved to the gathering of welcoming media before leaning on the wing and answering the Customs questions. Once the guys knew I was not smuggling people, drugs, food of various sorts or anything else illegal, I was good to go.

I spent another half an hour chatting away to the newspaper and radio. We then packed up the aircraft and headed for the motel. My stop in Hilo was scheduled to be one of the longest because of the scheduled aircraft maintenance; the plane needed a minor service every 50 hours and a major service every 100 hours. Finding a company permitted to carry out the service while I was there had been a logistical nightmare. Any country I visited when those hours ticked over had to have an organisation permitted to legally carry out the service. But we had finally found one who would do the 50-hour inspection, which included a minor oil change.

I threw my bags on the floor of another motel, turned on the air conditioning and decided to use my skills as a sleuth to find somewhere to eat. My diet of muesli bars had become quite old and I needed real food and I couldn’t drive anywhere so it needed to be close by. A large neon sign was glowing outside my window announcing ‘Ken’s 24-hour Pancake Parlour’. This detective work was too easy. I pulled on some shorts and a shirt and wandered over to Ken’s. I was barefoot, though not by choice; my shoes were still locked inside the aircraft.

I spent the next hour breaking down the world’s longest menu. It was something I could have studied for English in high school, and not a salad or muesli bar was in sight. As I sat at the long bar on a red speckled stool, peering through the mustard and ketchup, a waitress popped over to voice her opinion about my lack of footwear. I told her I actually didn’t have any shoes and although I promised to buy some from Wal-Mart later, food was my current priority.

I eventually shuffled from the diner to hail a cab, weighed down not only with a greasy American hamburger but the guilt of eating four days’ worth of calories, including a lifetime supply of fries. I stocked up on snacks to replenish my lunchbox as well as buying some thongs. (Note to self: They are called ‘flip flops’ in the USA. Thongs are a type of underwear that I have no desire to possess.)

As usual before bed I gave a quick update of the day’s flight to the team back home. With a few days off I had time to supply a little more detail. But first I needed a good night’s sleep – and that’s exactly what I had.

CHAPTER

13

The longest leg

After a very welcome sleep-in I called to confirm the 50-hourly service then I caught a cab to the airport. I started the Cirrus and warmed up the engine, readying it for an oil change, then taxied from Air Services Hawaii to Awesome Aircraft Maintenance on the far side of the airport. Immediately the guys began work, removing the engine cowls, draining the now blackened oil and inspecting each piece of the aircraft. I decided to hang around. The thought of 2200-odd nautical miles of ocean ahead of me was well and truly on my mind, and even with my limited mechanical knowledge I felt it was important to stare into the engine bay, hoping I was helping. If I thought it would be useful, I would have talked to the engine.

Everything went well, except maybe the lunchtime jaunt to Taco Bell, a Mexican diner where regret quickly overcame the short-lived pleasure of eating the food. I started the aircraft with the cowls, the covers to the aircraft’s engine, still removed for a quick test run. Everything seemed okay until something caught the mechanic’s eye. A pulley running near the rear of the engine bay was shaking vigorously, not something that should be ignored, so we shut the engine down and had a closer look. It turned out the air conditioning pulley had worn severely. We could have left it alone – air conditioning, though desirable, was not vital by any means – but it was intertwined with other systems in a way that meant it needed to be fixed.

After another call to Rex at Merimbula Aircraft Maintenance and a call to Cirrus on the USA mainland, we had a solution: to remove the complete air conditioning attachment now and have it seen to during the Cirrus’s major service which was scheduled to take place in Tennessee. This removed any risk that the issue could cause further problems on the long leg to California.

With the aircraft packed away for the night and after saying goodbye to the maintenance crew I headed back to bed. Bravely deciding to take on Ken’s Pancake Parlor once again I headed to dinner, this time in footwear: my not so cool pair of thongs purchased at Wal-Mart. I walked in and sat down in the same spot as the night before, and no sooner had I done so than the lady who had questioned my lack of footwear appeared, excited and very apologetic. It seemed the local newspaper had my face emblazoned across the front page that day. Not a lot happens in Hilo and the flight had become big news. This ensured that eating at Ken’s Pancake Parlor that evening was very different from the night before. I spent less time eating and more time talking, which was probably better for my long-term health.

After dinner I spent some time updating everyone with another blog. Thanks to Facebook and various other platforms, along with a live tracker on my web page, we were able to share the events of the flight with thousands of people from all over the world. A local from Hilo, Cam, had spotted the article in the newspaper and then discovered our Facebook page. He understood that I was not old enough to hold a US driver’s licence and offered to show me around the next day. With two more full days in Hilo and with the weather looking good, I was happy to take him up on his offer.

The next day I became a tourist, sort of. This turned out to be one of only four days on the entire trip when I set off purely with the intention of discovering a new place and seeing new things. All other days seemed to be riddled with jobs, phone calls, emails, flight planning, aircraft preparation or actually flying. Cam was a young university student who also worked in an observatory. We spent most of the day travelling around the Big Island together, walking through lava tubes and across the fields of dry lava I had seen from the air when I arrived. We found lava streaming into the ocean causing billowing steam to rise into the air, I was shown the volcano itself as we sat among tourists looking into the top of the crater and we watched the steam begin to glow orange as the sun went down.

Although I had a few phone calls it was a restful, casual day and I was grateful for that: I well and truly needed to relax before a final day of preparation and then the longest leg of them all.

I arrived at the motel late, climbed into bed and tried to get some sleep, a semi-successful undertaking. N

ext morning Shanna picked me up and we drove back to the airport to refuel and pack the Cirrus. Once again we took everything out of the plane and carefully stacked the equipment under the fuselage in the hope it wouldn’t blow away. The tank was nearly empty, but not completely drained. It was hard to pump absolutely all the fuel from the bladder while in flight; there was always a little fuel left in the bottom of the tank. As usual, when I arrived at the airport I had a page of fuel calculations in hand with exactly how much fuel I would like to have pumped into the bladder. Basically it would be filled completely this time.

Our calculations, standards and requirements of aircraft for the entire Teen World Flight had been based on the leg from Hawaii to the west coast of the United States, the longest part of the trip. If the aircraft could complete this leg safely it would have no issue with the others. It was a total of 2139 nautical miles or just short of 4000 kilometres, all over water. There was no dry land between Hawaii and California.

With the facts in mind and months and months of thinking about this one leg behind me, I started to refuel. I filled the main wing tanks to the brim before starting on the ferry tank. At the best of times filling the bladder required patience, filling too quickly caused the fuel to shoot up the filler pipe and make a ridiculous mess. Even when it was nearing three-quarters full only a trickle of fuel could be added at a time.

For nearly two hours I persevered with the refuelling, though I don’t think the guy waiting for me had the same level of motivation. Each time I was ready to decide the tank was full, I remembered the size of the ocean, shut up and kept filling.

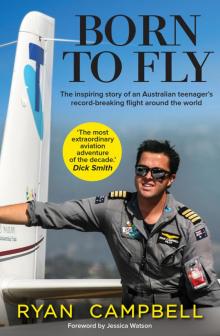

Born To Fly

Born To Fly